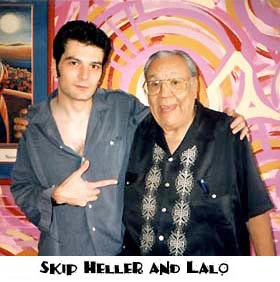

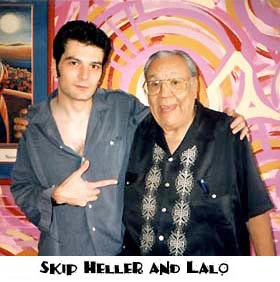

by Skip Heller

( Exclusive to Dana

Countryman.com)

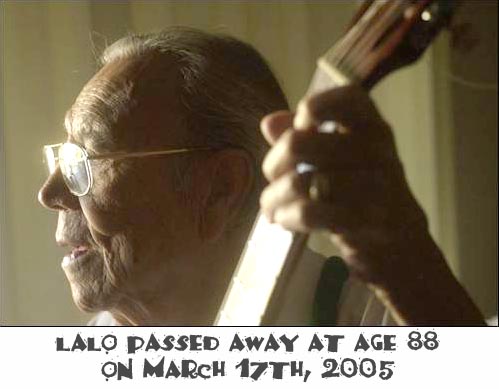

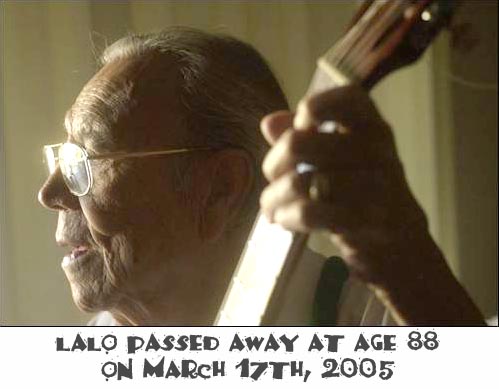

Mexican music legend Lalo

Guerrero passed away on March 17th, 2005, at the age of 88. The

trendsetting troubadour started a musical revolution in Latino

music that is still being felt today.

Skip Heller's article was

written in 2000, when Lalo was alive and still busy making

music.

It's July 17, a sun-drenched LA afternoon.

Just a stone's throw from the Police Academy is an annual picnic

to commemorate the mass dispossession of Mexican-Americans who

lived in Chavez Ravine until the area was cleared for Dodger Stadium.

The attendees fall into two groups those who were put out of their

homes, and their descendants. Sitting on a small bandstand, singing

in Spanish and strumming an acoustic guitar, is an old but still

charismatic Chicano man. The crowd receives him with wild applause.

They pay little attention to the skinny gringo next to him, who

is also playing the guitar, except to cheer after the guitar solos.

Afterward, the old man sits at a table beneath a shady tree, selling

CDs of his music. Members of the crowd walk up to him alone, or

with a family member. Unfailingly, each relates a story to him

about the impact his music has made on their lives. Everyone wants

an autograph.

"Lalo, my grandfather used to play me your records."

"Lalo, my wife and I met at one of your shows, fifty years

ago." "Lalo, can you make it out to . . ."

He listens and obliges each with a warm smile. These are his people,

and, like a benevolent monarch, he listens attentively to each.

the is no posturing nor pretense about him.

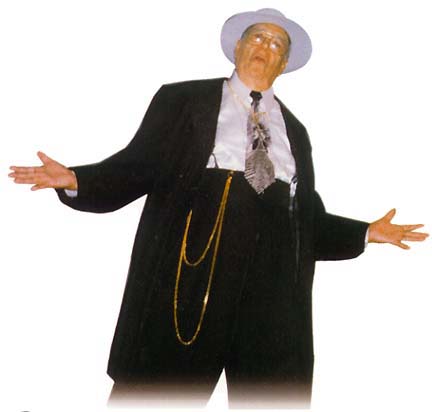

Lalo Guerrero, 82, is the father of Chicano music. Though he started

out recording typical mexican music in the late thirties, he soon

became the first to join Mexican-Spanish lyrics and slang to American

styles (swing, R&B), and his bilingual jump blues, such as

"Marihuana Boogie" and "Vamos a Bailar," are

classics, and were practically anthems to late-1940s pachucos.

"I used to play at a club at Spring and Macy that was very

popular with the movie crowd. Rita Hayworth and John Garfield

would come down there," he recalls. "And the other

thing we got was a lot of zoot suiters. They were really sharp-dressed

and clean not like the gangs of today. They loved swing, so we

played it, and also the conga, the rhumba and boleros the sad

love songs in Spanish.

"I recorded with a trio on Imperial Records, and I said,

`Why don't we write some swing songs in Spanish for these people?

Not only in Spanish, but in their kind of slang Spanglish'. They

loved it."

Guerrero's music jumped hard enough to reach past its intended

audience. I once dated an African-American woman who had inherited

her Uncle Adolph's collection of 78s. The uncle had worked on

Central Avenue in the forties, which was Black L.A.'s entertainment

hub. Adolph had a tidy little cache of Lalo 78s among his Roy

Milton's and Louis Jordan's. According to L.A. rhythm'n'blues

scholar/historian Jim Dawson, Lalo Guerrero was quite popular

with LA's African-American comminuty. I asked Lalo if the band

was racially mixed. His many 78s (cut for Imperial) during that

time range from typical mariachi to credible boogie woogie and

jump blues. The group was not, in fact, racially mixed. Impressively,

he used the same musicians on his sessions no matter what style

of music he brought to record. Their command of Latin, African-American,

and even white pop styles was unanimously credible.

"The band was all Latin, but our audience was 60 percent

blacks and whites. We did swing and boogie-woogie, but we also

did Latin, tropical. We mixed it up, and that's why people liked

it. At that time, L.A. was a very peaceful town. There wasn't

really trouble between the races."

Fittingly, Guerrero's jump tunes were featured throughout the

1984 musical Zoot Suit, which was both a stage play and a film

starring Edward James Olmos. He has a snazzy new CD on Break-Records:

Vamos a Baile Otra Vez (Get Out and Dance Once More)

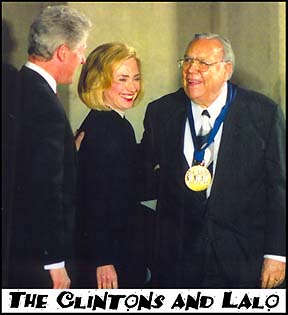

that focuses on both swing and Latin big-band styles. The Smithsonian

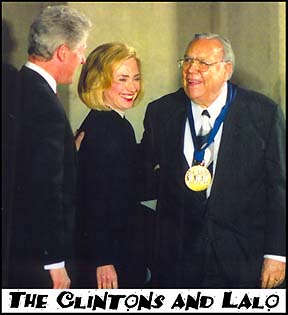

recently acknowledged Guerrero as a "national folk treasure,"

and President Clinton awarded him the National Medal of the Arts.

When asked if he was thrilled about getting medal, he shrugs.

"I guess so. They were giving one to Lionel Hampton the

same night, and I was more excited about meeting Lionel Hampton

and spending time with him."

(Sherilyn Meece Mentes told me that, one afternoon while she was

helping Lalo organize his papers, she found a sheaf of letters

of commendation. The certificate that accompanied Lalo's Medal

of Arts was in a stack along with certifcates from the Cathedral

City Ladted at the White House but doesn't really care that much

about it. He is regal, at ease and expansive. What purports to

be an interview turns into Lalo holding court. The warning signs

were there. When I told Nadine Trujillo, owner/self-described

Taco Nazi of the famed "hangout of the stars" Mexican

restaurant Alegria On Sunset, she insisted on making a traditional

Mexican breakfast with all the trimmings and asked if she could

have her picture taken with Lalo. Lalo told me he was going to

have a couple of friends meet him there, if that was okay. I said

fine, and an entourage showed up. His biographer, Sherilyn Meece

Mentes, Ben Esparza (the president of Break Records) and his wife,

and a couple of others.

I brought my pal Carmen Hillebrew, a lovely

woman with whom Lalo flirted throughout the meal. He also flirted

with any other woman in arm's reach, including Nadine. But, since

Carmen was at the table, she got the most attention. Although

happily married for many years, Lalo likes the ladies. I think

as much, Lalo just likes to play the part of the old wolf. Trying

to keep him focused enough to answer a question is hell. He is

attentive to everybody at once, which is not the greatest thing

in the world for what purports to be an in-depth interview. Eventually,

I just leave the tape recorder running. It's clear that he'll

tell the stories he wants to tell, clarify the points he wants

made clear, and pay attention to any female who gets within five

feet of him. He talks about how the young gangs of today trouble

him. The hell with scholarship. Let's get out our guitars and

play for the people eating breakfast, he suggests. When this happens,

the roomful of people suddenly takes serious collective notice.

And the vast majority of them, especially the older ones, are

pointing and saying "Omigodthat's Lalo Guerrero."

(This is restaurant whose regulars include the Red Hot Chili Peppers,

Beck, and various movie people. The clientele is generally pretty

blase about celebrity, so you know Lalo ranks as a legend.)

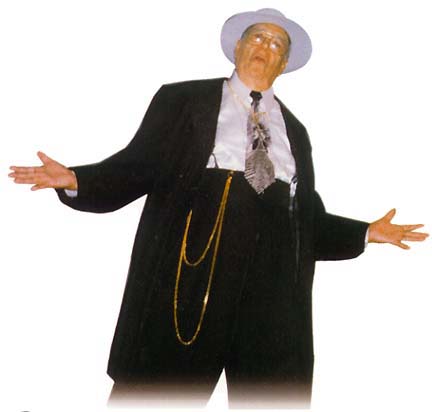

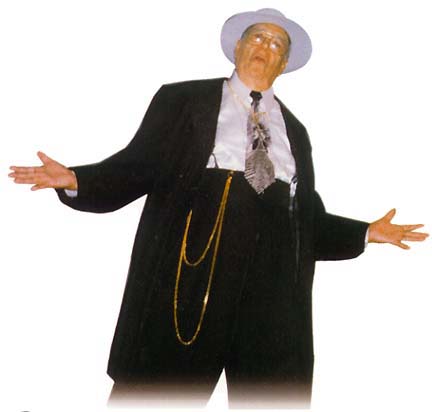

Even maybe especially in such an informal, intimate setting, Lalo

is 110% showmanship, and the set list he improvises consists mostly

of his song parodies about food. We play "Tacos For Two"

(his "Cocktails For Two" send-up), "I Love Tortillas"

(to the tune of "O Solo Mio"), and Mexican Mammas, Don't

Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Busboys". The small audience

is delighted and approves loudly. Their enthusiasm couldn't be

greater if the Spice Girls had showed up and staged an impromptu

wet t-shirt contest.

Guerrero's lyrics are often very pointed, which is atypical of

a performer of his generation. His famous parodies cover the INS,

low-pay food-service jobs, and youngsters deserting Mexican music

in favor of rock & roll. His other new CD, Tacos for Two:

Lalo Guerrero's Greatest Parodies (S.O.S. Records), features engaging,

buoyant recent recordings of such favorites as "I Left My

Car in San Francisco," "Tacos for Two" and "Mexican

Mammas, Don't Let Your Babies Grow Up To Be Busboys." While

Vamos shows his Cab CallowayonWhittier Boulevard side, Tacos is

all charm and mischief, capturing the most overt components of

Guerrero's personality.

Because Disney's music-publishing arm won't grant licenses to

parodies of songs to which they control the rights, Tacos doesn't

contain Guerrero's best-known lampoon, the 1955 "Pancho Lopez,"

which spoofed "The Ballad of Davy Crockett." Despite

the fact that  Crockett owed his celebrity to his shooting

Mexicans at the Alamo, the Crockett TV show was quite popular

with Chicanos. Pancho, on the other hand, was a lazy, siesta-addicted

Mexican who opens a taco stand on Olvera Street.

Crockett owed his celebrity to his shooting

Mexicans at the Alamo, the Crockett TV show was quite popular

with Chicanos. Pancho, on the other hand, was a lazy, siesta-addicted

Mexican who opens a taco stand on Olvera Street.

"I had never written a

parody before. I knew who ol' Davy was, so I decided to poke

fun. I recorded it first in Spanish, and it was a big hit, and

[Imperial Records president] Lew Chudd said that we would sell

a million if I recorded it in English, so I did. From the money

for that, I bought my nightclub, Lalo's, in 1963.

"At the end of the song, I

tell people to come to Olvera Street to see Pancho running his

taco stand. Tourists would come into Union Station and say, `Where's

Olvera Street?' and, of course, it was right near there. The

merchants loved `Pancho' because it told people to come to Olvera

Street, and they did."

After we're through entertaining the crowd at Alegria, Guerrero

asks me if I want to come with him and play a gig.

"Sure. Where?"

"Chavez Ravine," he answers. I thought he was joking.

I didn't know about the picnic.

As it turns out, this was indeed the day when, every year, the

enforced exodus is commemorated. I say sure. Sherilyn Meece Mentes

does the driving, and we almost lose our way in the hilly, winding,

almost circular streets of Echo Park.

When we arrive, a local amateur Latin jazz group is playing "Oye

Como Va". It looks less like a protest than a family reunion.

One thing about a bunch of Mexicans gathered together they definitely

want to listen to music and eat. I'm the only Anglo among the

500 or so faces, and every grandmotherly woman in the bunch (which

is a lot) is trying to get me to "eat a little something,

El Flaco [Mr Skinny]". They obviously went to the same Catholic

Grandmom School as my (Italian) grandmom.

This time when I hit the stage with Papa Lalo, his set list is

much different. And I'm nervous, because I've never played any

of the tunes before, and the entire crowd seems to be mouthing

the lyrics along with Lalo. The parodies of English-language hits

were easy for me. I know those songs like the back of my hand.

But when Lalo launches into "Corrido De Delano" a protest

song from the days of Chavez' leadership of the farmworkers' strike

and "Y Soy Chicano", I'm hanging on for dear life. I

barely know this chapter of the Guerrero songbook, and everybody

here but me seems to have committed it to memory. This set isn't

about rhythm'n'blues or comedy. This is folk music about people

being proud in the face of adversity. For this crowd, the set

mostly sticks to the theme of Chicano pride, with an occasional

parody thrown in. He speaks entirely in Spanish between songs.

The crowd loves him, and dearly.

Although regarded mainly as a parodist, Guerrero has made all

kinds of Latin music mariachi, boleros, banda, Cugat-esque tropical,

salsa and corridos. He's also cut credible records in many Anglo

pop styles (in English), and even a great deal of Spanish-language

children's music. In 1994, he joined Los Lobos for a children's

record, Music for Little People (which earned him his first Grammy

nomination). When asked if he ever worried about confusing his

audience, Guerrero shakes his head emphatically:

"No! Because I'm that kind of a guy I just want to write

something if I get inspired. Whether it's in English or Spanish,

a parody, a love song, swing . . . I don't mind."

While Lalo was busy in the sixties running and performing at his

club, Lalo's, the California farm workers went on their

famous strike. His Chavez-era protest songs are treasures, their

reportage of life in the San Joaquin Valley on a par with Merle

Haggard's best, their message of pride akin to Curtis Mayfield's.

"Corrido De Delano" is like a Chicano "Keep On

Pushing".

The alliance between Guerrero and Cesar Chavez began in an offhanded

way.

"When I first met him, in Delano, I was on the road with

my band. We'd go up north to Bakersfield, Fresno, Tulare, Merced,

Sacramento, San Jose. Cesar would come [to the clubs] with his

friends, looking for girls. He'd say, `Lalo, they're gonna be

picking onions over in Sacramento Valley' or `Lalo, they're gonna

be picking strawberries in Bakersfield,' and the pickers were

mostly Chicanos, so he'd tip me to where they'd be, we'd go there

to play, and sure enough, there would be a lot of people to see

us.

"He and I stayed close to the end, and of course, I played

some of the marches and met many of the people."

Guerrero played zillions of rallies of and benefits for the farmworkers.

He also used his celebrity to bring people's attention to the

harmful effects pesticides sprayed on the fruit had on the people

who made their living in the fields handling that fruit.

Leaving Los Angeles after he sold Lalo's in 1972, his plan

was to return to his hometown of Tucson, open a little Mexican

restaurant, maybe do a little strolling table-to-table with the

guitar. He got in the car intending to resettle. He didn't make

it. While driving through Palm Springs, he called his friend Gloria

Becker, a local booking agent.

"She said, `Lalo, I need you to play. They're opening

a beautiful Mexican restaurant here.' Well, they made me an offer

I couldn't refuse, and I stayed for 24 years. The pay was excellent,

and it worked out better than Tucson would have, because I don't

know anybody there anymore and I still have so much to do in

Los Angeles. I'm only two hours away, so I get here pretty often."

Guerrero still lives near Palm Springs, in semiretirement.

When KPCC disc jockey Sancho launched the Chicano Music Awards

a few years back, Lalo was the first recipient. Terrible at sitting

still, he was busy promoting his two new discs and playing wherever

he is asked, and a Lalo Guerrero Big Band concert was in the works

under Esparza's eye, but has not yet been staged. He recently

had made a music video in support of Vamos a Baile, and

a local newsmagazine show recently featured a segment on him.

He was an octogenarian perpetual-motion machine, and nothing about

him looked ready to slow down.

Guerrero still lives near Palm Springs, in semiretirement.

When KPCC disc jockey Sancho launched the Chicano Music Awards

a few years back, Lalo was the first recipient. Terrible at sitting

still, he was busy promoting his two new discs and playing wherever

he is asked, and a Lalo Guerrero Big Band concert was in the works

under Esparza's eye, but has not yet been staged. He recently

had made a music video in support of Vamos a Baile, and

a local newsmagazine show recently featured a segment on him.

He was an octogenarian perpetual-motion machine, and nothing about

him looked ready to slow down.

Although the sun beat down on us hard during

that forty minute set we played, Lalo is still buoyant as he sits

under a shady tree signing autographs, and, true to form, flirts

with every woman who comes within arm's length. He sips a light

beer and chit-chats with the musicians. After a couple of hours

of food, music, and talk, Sherilyn tells us we have to go. Lalo

nods in agreement, and we walk with her to the parking lot.

We stand at the curb with our instrument cases as she fetches

her car, and I tell Lalo he looks a little tired. The sun was

merciless onstage while we played, and even the shade tree wasn't

much protection after the fact. Lalo is tired, but he just shrugs.

"I love to be around musicians, around music. I don't tell

myself, `Keep active' or anything. I just love what I'm doing,

and lately I've been getting recognition, which feels very good.

I wouldn't try to stop something that feels so good."

- © 2000 Skip Heller

can be ordered directly with a

simple click on the CD cover

Special thanks to Benjamin Esparza

of Break-Records for use of the photos on this page

For more photos and informative

articles on Mr. Guerrero, please visit

www.break-records.com

Crockett owed his celebrity to his shooting

Mexicans at the Alamo, the Crockett TV show was quite popular

with Chicanos. Pancho, on the other hand, was a lazy, siesta-addicted

Mexican who opens a taco stand on Olvera Street.

Crockett owed his celebrity to his shooting

Mexicans at the Alamo, the Crockett TV show was quite popular

with Chicanos. Pancho, on the other hand, was a lazy, siesta-addicted

Mexican who opens a taco stand on Olvera Street.

Guerrero still lives near Palm Springs, in semiretirement.

When KPCC disc jockey Sancho launched the Chicano Music Awards

a few years back, Lalo was the first recipient. Terrible at sitting

still, he was busy promoting his two new discs and playing wherever

he is asked, and a Lalo Guerrero Big Band concert was in the works

under Esparza's eye, but has not yet been staged. He recently

had made a music video in support of Vamos a Baile, and

a local newsmagazine show recently featured a segment on him.

He was an octogenarian perpetual-motion machine, and nothing about

him looked ready to slow down.

Guerrero still lives near Palm Springs, in semiretirement.

When KPCC disc jockey Sancho launched the Chicano Music Awards

a few years back, Lalo was the first recipient. Terrible at sitting

still, he was busy promoting his two new discs and playing wherever

he is asked, and a Lalo Guerrero Big Band concert was in the works

under Esparza's eye, but has not yet been staged. He recently

had made a music video in support of Vamos a Baile, and

a local newsmagazine show recently featured a segment on him.

He was an octogenarian perpetual-motion machine, and nothing about

him looked ready to slow down.